In the last two years, every time I thought about the death of one of my cousins, I got upset. At the beginning, I put it down to bereavement grief, though I gradually realized it wasn’t related to the loss. My emotions were related to the deliberate exclusion from family connection. Every time when I tried to approach my cousins about the death, they responded with reticence or avoidance. Their closed door caused me deep pain. I dug deeper to understand why.

There were previous episodes of exclusion. When I was ten or eleven, I lived with this family. They provided for my physical needs as best as they could, and reminded me to treat their home like my own. However, my own set of habits and preferences, cultivated by my mother, were challenged in the new environment. I was either openly ridiculed or criticized, sometimes freely broadcasted to their friends or neighbors, because my ways did not agree with theirs. Their jeer might be intended as innocent fun, but it carried an unmistakable tone of non-acceptance.

In my home, my mom was the boss. In their home, I didn’t know who was my boss. Through errors and punishment (shame and guilt) I discovered that at least six out of seven of the household members had authority over me. Having to please that many people was too much and too conflicting, as one person would say one thing and another person would say another. I had to be on guard 24/7. Not only were my emotional needs as a child not met, I had to meet the emotional needs of everyone older than me.

Just being clean and tidy was not enough for this family. I was shamed precisely because I was different. I faced pressure to lose my individuality. Things that my mother had taught me were challenged, questioning my allegiance to my mother.

The inconsistent and confusing messages given to me by various members of this family were not affirming nor loving, and I grew up with a distorted concept of family, belonging, home, identity, trust, as well as losing my relationship with my own mother.

. . .

Upon the death of my cousin, I understood that it must be too overwhelming for her surviving siblings to talk about it, so I gave them space. I stood outside of their family, waiting, up until now, and realized, I should not be waiting in the first place. Their door would never open for me. I felt deeply hurt from being excluded.

They would open their door to me for other things, but not to a discussion about the death. Standing outside, alone, wounded, I felt helpless and rejected.

I questioned why I was so stupid to be waiting outside. I realized I was baited into it in the first place. The information they shared surrounding the death didn’t make sense. Processing an illogical story does not bring closure, because it’s not processable. Rather, it creates more questions, more rumination. That’s why I needed to approach them, several times, to seek clarification.

The second bait was me being told that there were strange things said on the last day before the death. Piquing my curiosity for two years, keeping it suspended but never satisfied, I wondered, ‘What kind of things? How were they strange?’ My cousin never elaborated. At this point, after several attempts to knock on closed doors, I didn’t want to ask anymore. I also didn’t know whether I had the right to know, because I didn’t know where I stood. Were the “strange things” too private, for someone who might or might not be a family member? Yet, the bait keeps dangling in front of me, as my cousin kept calling it “the strange things”, and each time when I heard it, I quietly salivated at the denied bait. A subtle way to remind me of being excluded.

I even asked myself, why did I choose to wait for them to open up? Why did I stare at a closed door? Why didn’t I just move on? More specifically, why this passiveness? I realized, it went back to my interaction with my mother where she was the center of my universe. She wouldn’t talk to me nor allow me to disturb her, but she would sit in the same room as me doing her own thing, and I would keep gazing at her, waiting quietly, hoping that she would eventually give me her attention. Rarely would she care to do so, and if she did, it was to punish me.

So I was activating this pattern of seeking and waiting for attention when my cousins closed their doors. Thus activating my wound of emotional neglect.

While waiting for my cousins to open up, I offered as much emotional support as they were willing to receive, but they never once asked me how I felt, as if I had no feelings, as if the deceased was never a connection to my own past, not to mention a total disregard of how I felt about standing outside and waiting indefinitely to be let in. Another emotional neglect.

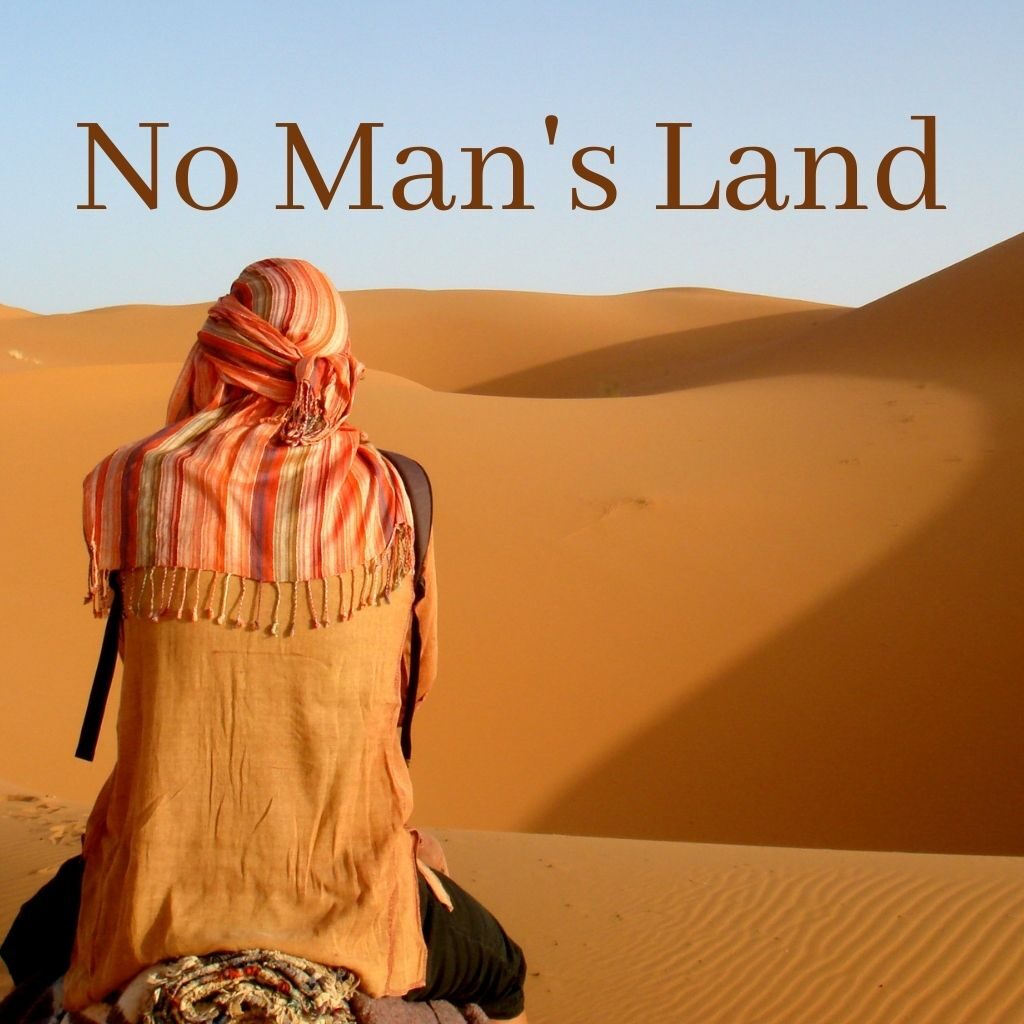

So while my relatives had their own grief to heal, I also had mine, activated by their closed doors. The more I heal my wound, the more I understand why I was feeling that way. I realized, deep down, I didn’t quite want to be included. I was standing in No Man’s Land, trying to protect myself from their mockery and disapproval, while at the same time hoping that I could receive emotional nourishment from them. Metaphysically, I had manufactured the exclusion. The pain I felt was ultimately created by me. By releasing the emotions that propelled me into No Man’s Land in the first place, I am opening myself to connect, to experience a sense of belonging, inclusiveness, and nourishing relationships.